Oregon Somali community speaks out on state of fear amid ICE raids in Minnesota

PORTLAND, Ore. (KATU) — As tensions in Minneapolis over the continued surge of federal immigration officers reach a boiling point, some Oregon Somalis say the rhetoric is starting to seep into their community and their children’s mental health.

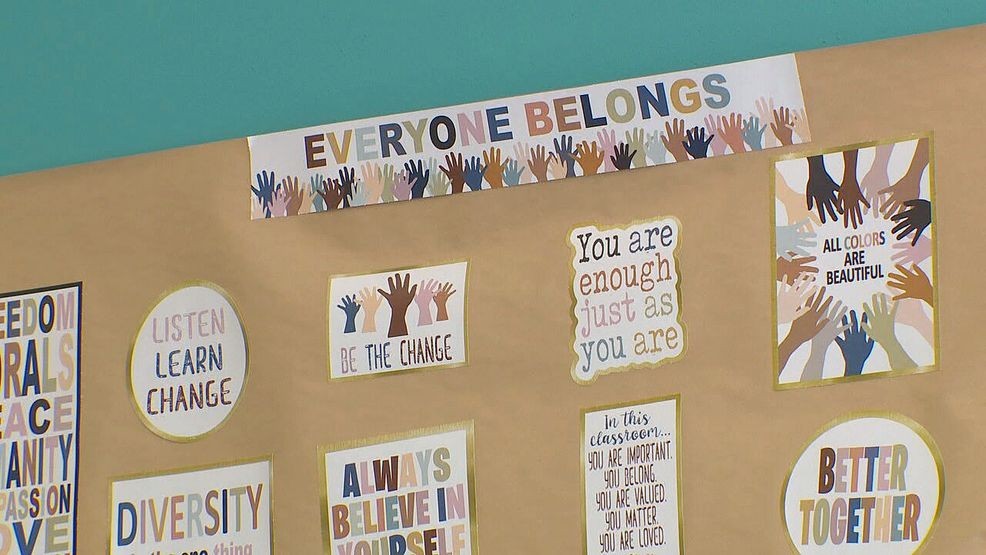

"Just last night, my son was saying, 'Mommy, they [ICE agents] can't come into our school, right? Because my teacher said they have a sign that they can't come to our school,'" said Sadia Noor, an American citizen of Somali decent. Noor is the executive director and founder of Next Gen Connect Center, a free after-school tutoring program.

The federal presence in Minneapolis surged after accusations of widespread welfare fraud in Minnesota proliferated in light of a viral video shot by a conservative livestreamer shortly after Christmas.

Minnesota has been under the spotlight for years for Medicaid fraud. One of the biggest fraud cases dates to the pandemic when a nonprofit called Feeding Our Future allegedly stole nearly $300 million intended to provide food for children. Further investigations uncovered additional alleged schemes.

First Assistant U.S. Attorney Joe Thompson has recently claimed the Medicaid fraud scheme could amount to around $9 billion in losses to taxpayers. Many of those charged in the multiple schemes -- 82 of the 92 defendants -- are Somali Americans.

The state is home to the nation's largest percentage of Somali Americans, most immigrated as refugees after the Somali civil war, and many are now citizens or second-generation Somalis born in the U.S.

The issue came back into the spotlight during President Donald Trump's immigration crackdown, with the administration's officials launching an investigation into whether some of the funds were diverted to the terrorist organization Al-Shabaab.

Noor believes that anyone who is convicted of fraud should face the consequences but is frustrated with rhetoric that paints the entire American Somali community as complicit in fraud.

"I never felt unsafe my whole entire life of being in America till now. Yes, the fraud cases or fraudulent situations did happen. Does that mean everybody should be judged the same? Should my whole community be dragged through the dirt and the mud and be attacked?" she said.

Noor came to the U.S. around the age of six after spending time at one of the massive refugee camps set up along Somalia's bordering nations during the civil war. She also has some memories of U.S. intervention in the war prior to her fleeing with her mother.

"I remember that we were there during Black Hawk Down. I remember that and I'm pretty sure I was very young, because I remember the American tanks that would drive by. I remember that specifically because every time those tanks drove by our home, our street, I remember me and my other neighbors’ kids or friends running to those tanks because they had little goodie bags for us," she said.

She said her desire to open an after-school tutoring program came from her own difficulty learning English while attending school and being inspired by the support she received from school staff. According to IRS filings, her nonprofit founded in 2024 makes less than $50,000 a year in revenue.

The drop-in center she operates is provided to her for free as part of the community space in the apartment complex she lives in. Most of the estimated 26 kids she tutors with support from parent volunteers live in the complex. She estimates that about 80% are Somali and the rest are from all over, many are also Latino. She said she has received small grants and continues to apply for more to help her continue this work which is her full-time job.

She noted that the family she serves has been discussing a sense of growing fear and pointed out that their children continue to ask questions that indicate fear of deportation or being detained, even when they and their family members are citizens.

"Even though most of us are U.S. citizens here and been in the states, again, I'm sure there are people who have been here even longer than I've been, and we still have that fear and whether we'd like to admit it or not, we are carrying it around daily because you don't know what's going to happen. If it's not me, it's gonna be my neighbor. If it's not my neighbor, I know it's gonna be somebody I know or am related to somehow. I'm just like really hurting for my community right now," she said in tears.

She said her two nephews who are students at Portland State University have recently been harassed and even chased by groups of individuals filming them and calling them "Ilhan Omar," a U.S. representative of Somali descent.

Two of her friends have recently been harassed while shopping with their 11-year-old daughter and were told to go back to their country.

"The Oregonians I know and that I grew up with, I would never think would do such things or act such ways," she said.

KATU reviewed a recently posted video on social media where an individual filmed a small non-profit Somali community drop-in center in Portland, insinuating its activities to be nefarious because it was closed one week after Christmas.

When contacted, the small nonprofit, which according to IRS tax filings also makes less than $50,000 in revenue mostly through private grants, told KATU that it is volunteer run and as such has limited operating hours and most of its funding goes to pay for food that it provides to the community at weekly food giveaway events.

The individual who posted the video removed it after a discussion with the nonprofit about its operations. The individual did not respond to a request for comment from KATU News.

Incidents like these have prompted a number of Somali community members to speak out, telling KATU News they want to stand up for their community.

"The kids are right now feel unwelcome in their community because of what they are hearing. They hear their parents are labeled as fraudulent or they are not doing things that they are supposed to do. They carry fear with them and that's impacting us a lot," said Abdifatah Abdurahman, president of the Southwest Somali Community.

He noted that some members of the community have said their children are coming home from school asking their parents if they are fraudulent.

Zam Zam Abdulle, a community outreach volunteer with Southwest Somali Community, says she has spoken to Somali Oregonians that are keeping their kids out of school despite being in the country legally, because they fear they will be detained.

"There are kids, their moms are United States citizens, and they have to stay home and do some schooling at home, and they cannot go to school. And explaining to the kid that they cannot go to school anymore because of their parents’ status is just a little bit hard and is putting a lot of stress on them," she said, noting that the community fear is based on reports that some American Citizens in Minnesota have been detained despite their citizenship status.

"We don't, as a community, know how to stay safe mentally and inform our kids and elderly at the same time. You can now go to a 6-year -old and tell them that the president doesn't like us anymore and we can do nothing about it, and we have to stay home, especially when they were born here, and they're from here," Abdulle said.

All three urged people not to buy into the rhetoric and urged their fellow Somalis to reach out for support.

"We're all eventually hopefully gonna get through this one day and look back and nobody's gonna laugh about it, but at least we'll know that we made it through," Noor said.