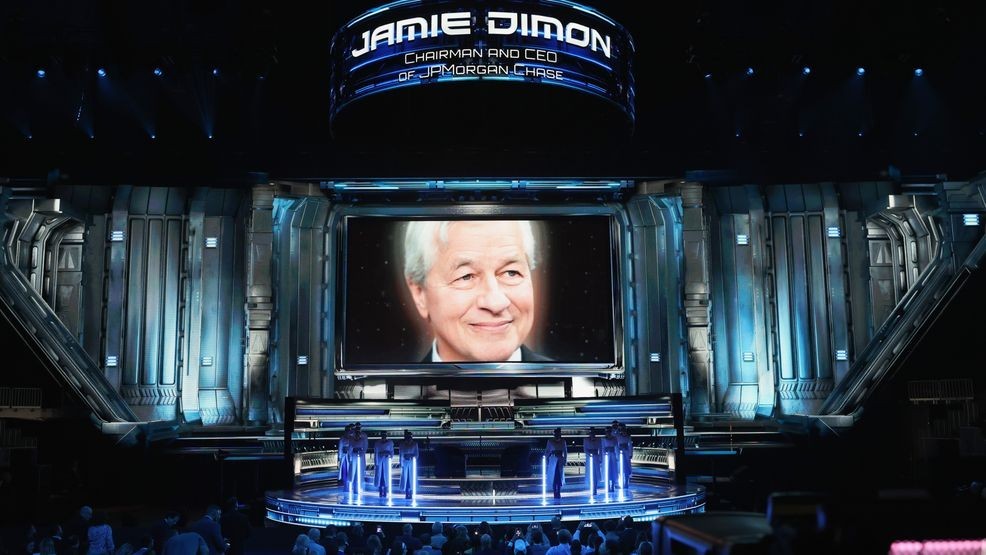

Fact Check Team: Exploring Trump's political debanking lawsuit against JPMorgan Chase

WASHINGTON (TNND) — President Donald Trump has filed a $5 billion lawsuit against JPMorgan Chase and its CEO, alleging the bank shut down his accounts for political reasons in the aftermath of the January 6 Capitol riot.

At the center of the lawsuit is the claim of political debanking, the idea that Trump’s accounts were closed solely because of his political views. (TNND)

At the center of the lawsuit is the claim of political debanking, the idea that Trump’s accounts were closed solely because of his political views. Trump’s legal filing argues that the account closures amount to political discrimination and an abuse of financial power. JPMorgan Chase denies these claims. In a public statement responding to the lawsuit, the bank said it does not close accounts for political or religious reasons, but instead when accounts pose legal or regulatory risks to the institution.

“Our company does not close accounts for political or religious reasons. We do close accounts because they create legal or regulatory risk for the company,” JPMorgan said, adding that “rules and regulatory expectations often lead us to do so.” -JPMorgan Chase statement, January 2026

That response points to a larger issue underlying Trump’s lawsuit: what banks are actually required, and allowed, to do under federal law.

Do Regulations Prevent Debanking?

There are federal rules governing how banks treat customers, but those rules are often misunderstood. Agencies like the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau prohibit unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts, but they do not require banks to keep accounts open indefinitely. According to an analysis by the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, debanking is a serious problem affecting at least thousands of consumers, and resulting in substantial hardships for consumers and businesses.

The Senate report notes that while regulators could strengthen consumer protections, such as limiting broad debanking clauses or improving remedies for erroneous closures, existing rules are largely designed to protect financial institutions and the government from risk, not to guarantee banking access for customers.

What the Data Says About Debanking

Trump’s lawsuit comes as renewed attention is being paid to whether banks are discriminating against conservatives or religious groups. A new study from the Cato Institute suggests the reality is more complicated.

After reviewing public cases and complaint data, Cato concludes that most debanking is not driven by political or religious discrimination, but by government pressure on banks, both direct and indirect.

“The majority of cases over time can be found where government officials have intervened in the market by either directly or indirectly telling banks how to run their business,” the report concludes.

The study describes banks as being caught in a bind: federal law requires them to monitor customers for suspicious activity, but other laws prohibit banks from telling customers why their accounts were closed. That lack of transparency often fuels accusations of discrimination, even when closures are tied to compliance concerns.

That response points to a larger issue underlying Trump’s lawsuit: what banks are actually required, and allowed, to do under federal law. (TNND)

Four Types of Debanking

Cato’s analysis breaks debanking into four categories:

- Governmental debanking: when government agencies pressure banks to close accounts

- Operational debanking: internal business decisions, such as contract violations, overdrafts, or reputational concerns

- Political debanking: closures based solely on political beliefs

- Religious debanking: closures based solely on faith

According to the study, governmental and operational debanking account for the vast majority of cases, while purely political or religious debanking appears to be rare.

Are Conservatives Being Targeted?

To test claims of political or religious targeting, Cato points to a review conducted by Reuters of 8,361 account-closure complaints. Only 35 complaints mentioned words like “politics,” “religion,” “conservative,” or “Christian.”

Cato argues that context matters in high-profile cases, including Trump’s. Many prominent account closures occurred during periods of active criminal or civil investigations, often alongside reports that federal law enforcement was pressuring banks to reduce risk exposure.